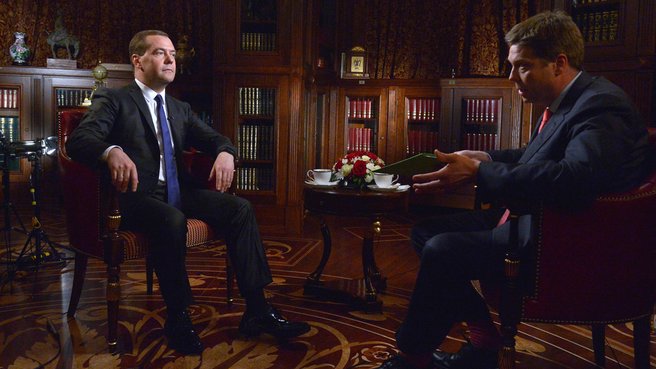

Dmitry Medvedev spoke with Bloomberg’s Ryan Chilcote on natural gas supplies to China, the political situation in Ukraine and US sanctions against Russia.

Transcript:

Ryan Chilcote: Prime Minister, thank you very much for joining us. President Putin has gone to China. One of the contracts that may be signed there concerns gas, and supplying gas to China. How likely is it that a deal can be done?

Dmitry Medvedev: Good afternoon. I'm glad for the opportunity to be interviewed by Bloomberg once again. It seems just a short time ago that we met in Switzerland. This time, it’s hot in Moscow. It’s nice when the warm weather arrives.

As for gas relations between Russia and China, we have been holding talks on supplies from Russian gas fields to China for quite some time now. There are two possible routes: one is called the Eastern route, and the other the Western route. These were not the easiest talks, since one side always wants to sell for a higher price, while the other wants to buy for a lower price. However, I believe it is very likely that there will be a contract, which means long-term agreements. The sides have agreed that it should be robust strategic cooperation designed to last for many years. The wording will be finalised very soon. I believe it’s time we reached an agreement with the Chinese on this issue.

Ryan Chilcote: The price that China will pay for the gas that Russia supplies it is less than what the average country in the European Union pays. Why does it make sense for Russia to charge China less than European countries? Is it because Russia wants to diversify its export markets?

Dmitry Medvedev: First, and this is very important – we haven’t signed the document yet.

Second, the price is never fixed when it comes to gas cooperation. The price is calculated according to a specific formula, and it depends on the volume of gas sold and the distance it is transported, that is, the pipeline system, that length of pipeline that makes up this transit line. Of course, it depends on the quality of gas, and on other factors, including the replacement of gas with other types of fuel. The calculations are usually based on so-called gasoil, coal or something else. So it is very complicated. This is the second thing.

And finally, third. I am absolutely certain that these prices will be comparable. But clearly, delivering to Europe is one thing and delivering to a new market is another. To attract a new market and to agree on all terms of collaboration, a variety of means is used to stimulate deliveries, including advance payments, bonuses and so on. All these factors are taken into account when establishing rates. I believe that in the long run the price will be fair and totally comparable to the price of European supplies.

Ryan Chilcote: But it's very important for Russia to have China as an export market.

Dmitry Medvedev: Of course, without a doubt. We value our European partners very much. We have worked with them for decades. It is a very important and very valuable market. I want everybody to understand that. On the other hand, we cannot supply our gas to the European market alone, because we have enough for the Asian market, which is the most rapidly developing market, including China, a major economy.

Ryan Chilcote: Especially if Western Europe, the European Union, is constantly saying that they want to diversify away from Russian gas, right?

Dmitry Medvedev: No.

Ryan Chilcote: This is a way of handling your problem with western European threats to diversify from Russian gas.

Dmitry Medvedev: It’s not because we attach much importance to statements of this kind. First, each country or group of countries, including the European Union, has the right to diversify their supply sources. This is true. But we don’t attach much importance to this simply because, so far, there is no viable alternative in sight to Russian supplies. We just happen to think that we, as a major energy-supplying power, must have an opportunity to deliver gas not only to Europe but also to Asia. We are benefitting from this. Today, I wouldn’t look for politics behind this, but I have no doubt that supplying energy to the Asia Pacific Region holds out a great promise in future. More than that, we have enough capacities and enough gas to send supplies via both the eastern and the western routes. But even if we look at the worst prospect – purely theoretically – any undelivered European gas supplies can be sent to China by the eastern route. But that, let me stress this point again, is so far an absolutely theoretical possibility.

Ryan Chilcote: If western Europe was to move away from Russian supplies…

Dmitry Medvedev: You know, all this talk is absolutely abstract or politicised in nature. Some of our partners, including in the United States of America, say: “We’ll heap you guys in Europe with LNG.” OK. Let them give us the calculations. As far as I understand, even if this is done on a very balanced basis, the price of LNG to be supplied from the United States of America will be 40% more expensive than the Russian pipeline gas.

Ryan Chilcote: What do you think about the idea of selling Rosneft stock to a Chinese company?

Dmitry Medvedev: To begin with, Rosneft is one of our biggest free-float companies, so some of its stock already belongs to foreign shareholders.

Ryan Chilcote: BP has a 20% stake, it’s the world’s largest crude oil producer that is publicly traded.

Dmitry Medvedev: Absolutely. So BP has some stock to begin with. Second, every deal should bring benefits primarily to the company itself. We are trying to make steady our energy market. In the final count, Rosneft should decide for itself what development sources to use. If Chinese investors make an interesting proposal, we don’t rule anything out. In any event, the Government is planning to privatise a considerable amount of Rosneft stock.

Ryan Chilcote: In this year? You want to sell a stake in 2014?

Dmitry Medvedev: For the time being, we spoke about next year and even 2016 but we may return to the issue this year.

Ryan Chilcote: What would be the point in selling a stake in Rosneft this year? Because when it comes to privatisation, so far everything has been pushed back, and now you are talking about moving privatization of Russia’s largest oil producer forward. It’s a bit surprising. Markets aren’t very nice…

Dmitry Medvedev: Yes, you’re right, so before making а decision on privatisation, we must weigh all factors before taking any decision regarding privatisation, primarily the stock price, which is to say how much privatisation will fetch. Our goal is to maximise revenue. That said, you can’t keep putting off privatisation because you think prices will be higher in 2015 than in 2014, or in 2016 rather than in 2015. Research needs to be done, and this kind of analysis and research is being carried out.

Ryan Chilcote: What do you think about opening up the Russian economy – and Russia in general – more to China?

Dmitry Medvedev: China is already a major trade partner of Russia, second only to the European Union.

Ryan Chilcote: But you have very big plans to increase China’s role in the Russian economy.

Dmitry Medvedev: That said, just recently – a week ago in fact – I held a special meeting with ministers and corporate leaders on promoting cooperation with the Asia-Pacific Region, which to a large extent means cooperation with the People’s Republic of China. We view this cooperation as critically important for Russia, and we believe it has great prospects in terms of expanding trade and attracting investment. These are issues that will be on the agenda of the Russian President’s talks with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Ryan Chilcote: For many years, Russia was very concerned about opening up its economy more to China. In the Far East, there aren’t that many Russian there; China is nearby.

Dmitry Medvedev: We always try to analyse what would happen if we enter a certain market, just like all countries do. There are commissions that issue permits for foreign investment in the United States, Europe and Russia. By the way, as prime minister, I chair the government commission on foreign investment. This doesn’t mean that we don’t deny permission, but we should understand where we can invite investors, including our Chinese partners. Again, we view China as our strategic partner and a very promising market.

Ryan Chilcote: Are there some parts of the Russian economy – “Red Zones”, if you will – where Russia would prefer China is not?

Dmitry Medvedev: I wouldn’t phrase it like this. The issue doesn’t concern Chinese investment alone. I’d put it as follows: Will there be some red lines beyond which we won’t allow foreign investors, like the majority of countries do? Yes, these are sensitive technologies, primarily weaponry. I think we have the right to keep some sectors under government control, but the number of such sectors keeps decreasing, and the commission I have mentioned takes decisions to expand the opportunities for foreign investment at almost every meeting.

Ryan Chilcote: Do you think that China could actually replace, let’s say, the European Union as a trading partner?

Dmitry Medvedev: But why? We are doing just fine as it is. We want to have a good relationship with Europe. Our sales turnover is over 400 billion. We also want strong collaboration with China, India, Japan and other countries. The idea of any politically motivated scenario is simply conjecture. The fact is, we want to trade in both the west and the east. Do you remember what the Russian coat of arms looks like? The eagle is looking in both directions.

Ryan Chilcote: You've threatened to cut of Ukraine's gas supply if they don't pay by the beginning of June. What exactly would you like to see Ukraine do?

Dmitry Medvedev: When you lend money to someone what do you expect to get from them? Kisses, promises, something else? I think any creditor is entitled to get their debt repaid. Therefore, we expect to receive the repayment of the debt that has accumulated over this time from Ukraine and the respective company.

Ryan Chilcote: And that is?

Dmitry Medvedev: It is more than $3.5 billion.

Ryan Chilcote: So you want them to pay the 3.5 billion?

Dmitry Medvedev: I spoke about this recently – we are realists. We are aware of the current state of the Ukrainian economy. We aren’t saying they have to pay 3.5 billion in a day, but give us a time-table for paying off these debts, especially since Ukraine has just received an IMF tranche, and both the Americans and Europeans have promised it loans. Let all countries that sympathise with Ukraine help it to pay off these debts. Allow me to recall how the situation has unfolded. As of 1 January of this year we have received practically nothing from them, even despite the preferential price. They pay us nothing, even with discounts. Now we’ve stopped giving them discounts and have said the following: “We’re ready to discuss different terms, but you have to pay your debts”, which now constitute a huge amount.

Ryan Chilcote: Ukraine was paying $268 per 1,000 cubic metres, correct?

Dmitry Medvedev: Only for three months.

Ryan Chilcote: The Ukrainians were paying $268 per 1,000 cubic metres. Now you're asking them to pay $485. That's a bit tough, isn't it?

Dmitry Medvedev: No, it's not tough simply.

Ryan Chilcote: That's more than any other country pays, with the exception of Macedonia, I think.

Dmitry Medvedev: We’ve already discussed the pricing formula. This is the price that was fixed in the contract signed in 2009, and it determines the cost of all supplies. This price is comparable with other formulas that are used for supplies to the European market – sometimes it’s more, sometimes less, but all of them are in line with the trend. As for $268.50, it is absolutely a discounted price, and so when we hear, “We are prepared to pay a discounted price,” our reaction is, why should we agree? Why do other countries, all the EU countries, pay a different price?

Ryan Chilcote: The European Union doesn’t pay $485 on average. The European Union pays $385. So you’d be charging the Ukrainians more than all of Western Europe.

Dmitry Medvedev: No, you have to consider how much each country pays. Some countries pay nearly as much. It is indeed a high price, I agree, but some countries pay this price, while other countries pay less. But again, it is an absolutely fair price that was agreed at the talks in 2009. We didn’t force anyone to accept it; they signed the schedule and the contract voluntarily. I’d like to remind you that it was Yulia Tymoshenko, who is currently running for president, who signed it.

Ryan Chilcote: The question is: Is the price for Ukraine negotiable? Will you demand $485 – more than most of the countries in Western Europe pay – of Ukraine?

Dmitry Medvedev: This is our position: There is a contract in place, but we understand that Ukraine is in a difficult situation. What should the de facto Ukrainian authorities do? They should present a debt repayment schedule and pay a reasonable part of the sum, which means repay part of the debt…

Ryan Chilcote: How much?

Dmitry Medvedev: That we can discuss, but it can’t be 3%. It should be a substantial sum that would clearly indicate their intention to pay their debts. After that, we could sit down to discuss gas cooperation going forward.

Frankly, we, including the Russian Government, have no intention to help the Ukrainian officials because we do not consider the current authorities to be legitimate and because they have not proved themselves as honest and sincere partners. But our hearts are bleeding over what is happening in Ukraine and what is occurring with the people residing in the country. So, we are prepared to discuss any collaboration as a humanitarian act. What we expect in return is an intention for serious collaboration and an intention to pay.

Ryan Chilcote: Can Western Europe count on getting all of the Russian gas that they’re expecting to get this year?

Dmitry Medvedev: If the Ukrainian market is stable and if Ukrainians fulfill all of their obligations, Europe will receive what it is entitled to in full. But we can’t ignore the fact that Ukraine stands between Europe, the European Union, and Russia. Our task now is to settle the situation around Ukraine. This task includes agreeing on gas supplies to Ukraine. If we succeed, everything will be fine. I would like to note, though, that Nord Stream is a guarantee that – for Europe – everything will remain as before. If we are able to commission South Stream in the next few years, then strictly speaking we won’t need to ship gas through Ukraine, although we realise that Ukraine might well need it. But if we get this done, the Europeans will have guaranteed access to gas at all times regardless of who’s in power in Kiev. There have been many different people in charge in Kiev lately, and I’m not at all sure that we can predict, with any degree of certainty, who will be running Ukraine even six months from now.

Ryan Chilcote: President Putin has ordered Russian troops back to their bases now that these so-called “springtime exercises” near the Ukrainian border are over. Considering that the last time that he made that announcement, the US and Germany couldn’t confirm that there was any pullback, why should anyone take this as anything more than a bluff from Russia?

Dmitry Medvedev: I don’t think we should worry about the reaction of Western countries to such statements.

What do Western countries have to do with our relocating troops within the territory of the Russian Federation, if we do so within the established rules?

Ryan Chilcote: Because Russia says it is interested in deescalating the situation in Ukraine. That's why.

Dmitry Medvedev: If you put the question that way, then this is an issue that should be analysed by those responsible for addressing it. It is President Putin who takes the decision to end exercises as Commander-in-Chief. Such a decision falls within the authority of the Russian state and its President.

Those monitoring troop movements can go ahead and request the relevant information. When I was in charge of these issues as Commander-in-Chief we naturally shared such information, and I’m confident that the current Commander-in-Chief will do the same. However, make no mistake, when and where to hold military exercises is, in the end, Russia’s internal affair.

Ryan Chilcote: Will Russia annex any more parts of Ukraine?

Dmitry Medvedev: First, we did not annex any part of Ukraine. This is the Russian position. If you're referring to Crimea, the situation is radically different. The population of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea held a referendum and voted for self-determination and for joining Russia in accordance with the existing procedure. And that's what they did. They started by proclaiming independence and after that, they asked to join Russia. We satisfied their request. The Russian Constitution was amended so that Crimea could join Russia as the result of a popular vote. Crimea is a special and unique story.

Any conjectures about Russia wanting to annex some territories are mere propaganda. I don’t even wish to comment on that. It is essential to calm tensions in Ukraine. We all see what’s happening there: the situation is nothing short of a civil war, as a matter of fact. This is what we should all be thinking about.

Ryan Chilcote: Can you guarantee that any other parts of Ukraine – in the east or in the south, where some separatists have asked for their territories to become part of Russia – that none of these territories, no more territories, will actually be joined to Russia?

Dmitry Medvedev: Let me repeat once again that first and foremost, we (I’m referring to all those who sympathise with Ukraine – European countries and as far as I understand, the United States and, of course, Russia, which is the closest to Ukraine) should do all we can to de-escalate tensions – a measure that everyone is talking about now. In other words, we should do everything to stop the spread of civil war on Ukrainian territory.

As for the positions of people in Lugansk, Donetsk and other parts of Ukraine, our stance is simple – their positions deserve respect. If they hold some referendums, we should understand what they want and why they express such views. So in the future, the main point is to make sure that Ukraine’s central, de facto authorities and those who live in these parts of Ukraine establish a fully-fledged dialogue based on mutual respect and understanding, a dialogue that takes into account the position of eastern Ukraine. This would ease tensions; otherwise the conflict will continue, and we will most likely hear the same appeals that were discussed at the referendums.

Ryan Chilcote: I'm asking a really simple question. Can you guarantee that the Lugansk Region, the Donetsk Region, won't become part of Russia, and will remain part of the territorial integrity of Ukraine?

Dmitry Medvedev: First, we don’t have to guarantee anything to anyone, because we never took on any commitments concerning this. But we believe that…

Ryan Chilcote: Would you like to take this opportunity to say, "No, Lugansk and Donetsk will never be part of Russia"?

Dmitry Medvedev: We believe the priority is to ease tensions in Ukraine. Not to guarantee something to someone, but to ease tensions. Let our partners in the dialogue, namely the EU and the United States, guarantee us something, for example, that they won’t interfere in Ukraine’s internal affairs. Let our Western partners guarantee us that they won’t lure Ukraine into NATO, that the Russian language won’t be prohibited in eastern Ukraine, and that some senseless movement such as the Right Sector won't start killing people there. Let our partners guarantee this.

However, this is not the way to talk, in terms of who should guarantee what. The conversation should be different, and this is what Geneva was all about. It must be willing to reassure people so that the de facto authorities in Ukraine actually must guarantee – not Russia – but the Ukrainian authorities must guarantee to their people that the crisis in the east will be resolved and that they will not use heavy weapons, including tanks, planes, and helicopters, against their own people. This is what they must guarantee. They should sit down and talk about the future – how the authorities in Kiev see it, and how it is seen by people in the east.

Obviously, there is considerable discord on this point. What does Kiev say? Kiev says, “We are a unitary state, and we must remain one for all time.” What do people in the east say? “We cannot exercise our rights in a unitary state. We want to speak Russian. We want to be more independent, including economic independence. We want guarantees that we won’t be wiped out by crazy nationalists, that they won’t come force us to take up weapons again.”

There needs to be a dialogue that results in a new constitution, but we are not imposing anything, because this is an internal process that must play out in Ukraine. However, we can see that the existing legal framework is not sufficient to solve this problem. As I understand, even some people in Kiev have started saying this. I hope it’s a good sign.

Ryan Chilcote: Will you recognise the presidential election in Ukraine?

Dmitry Medvedev: This is a complicated subject. On the one hand, from a legal standpoint, judicial terms, these elections are the result of an anti-constitutional change of power. You know Russia’s position – nobody has deprived Yanukovych of power. He hasn’t been impeached and he hasn’t resigned on his own free will. He’s alive, so he is the president and this is why we don’t recognise the legitimacy of some of the current authorities, at any rate the government and the acting president. However, we do realise that Ukraine has a legitimate parliament. On the one hand, elections are a direct consequence of these events, but, on the other hand, they may lead to a way out of the predicament. If an elected leader enjoyed the support of all of the regions in Ukraine, this would be good. But there is one more problem in addition to the low legitimacy of the elections. The problem is that some regions simply don’t want to participate in them. This may create a very complex situation where some regions take part in the elections and others won’t take part or will have a very low voter turnout. In this case, the value, the legitimacy of the elections, will indeed be called into doubt.

Ryan Chilcote: But it’s a very small part of Ukraine that wouldn’t take part in the election, right? There is 45-46 million people in Ukraine. You’re talking about two or three million.

Dmitry Medvedev: I don’t know how many people will attend these elections and how active they will be but I assume that the turnout in Kiev will be higher than somewhere in Lugansk, Mariupol, Kharkov and Donetsk. Some people will simply ignore the elections, because they believe they are not legitimate.

Ryan Chilcote: You recognised when the separatists held their elections in Donetsk and Lugansk, despite the fact that there was fighting, Russia said it respected the result of those referendums. Does that mean that you can respect the result of the national elections?

Dmitry Medvedev: There’s no contradiction at all. You are experienced in dealing with these issues and are good at analysing what is being said. Recognising results is one thing, respecting the expression of will is quite another. During the May elections, people in Ukraine will vote for different candidates. Of course, this position warrants respect. Is that an act of recognition? No, it’s not. However, such a decision constitutes an act of recognition, when the authorities of a foreign state say they believe these results clearly demonstrate the expression of will of the overwhelming majority of the citizens of a particular state. The Russian Federation has monitored elections many times in many places. Unfortunately, given the current situation in Ukraine, we can’t be sure that these elections will be held in a proper manner.

Ryan Chilcote: Can you imagine a situation in which the presence of Russian peacekeepers would be necessary, although, as far as I understand, Ukraine would not view them as peacekeepers. Could such a need arise in the future?

Dmitry Medvedev: You know, what I can say is that this is not a question of where peacekeepers come from. The question is about effectively separating conflicting parties in order to put an end to a situation where the army is being used against its own people.

What is the Kiev government, the so-called de facto authorities, speaking about? They are pretending to be fighting against terrorists. However, they are actually fighting against their own people in eastern Ukraine. The question is not what forces are being used and what mandate the peacekeepers have, but whether such forces actually make a difference.

Ryan Chilcote: What effect have the sanctions that have been introduced against Russia thus far had on the economy?

Dmitry Medvedev: You know, to put it simply, no one is happy about sanctions, since they are always a sign of tense relations. We don’t support the sanctions. Moreover, you’ve probably noticed that we have not commented on them a great deal or responded to them harshly, although we probably could cause some unpleasantness for the countries that are imposing these sanctions. But it’s bad for international economic relations, for our relations with Europe and the United States.

As for their direct impact, contrary to what the media and some Western analysts say, the sanctions have not had a significant effect on us. That doesn’t mean that we are happy about them. Again, sanctions are a dead-end, and, in fact, everyone understands this – everyone, including businesses in Europe and America.

Let’s be honest, these sanctions are a sharp knife for European business, and American business doesn’t need them either. The only ones who want sanctions are politicians, who use them to reinforce their convictions and to demonstrate their power. For example, our American colleagues and President Obama need to show the Congress that America doesn’t fear the Russians, that if anything happens they can hurt us. They need to show that the US President can take tough decisions, or rather that he is doing everything the Senate accuses him of not doing. This is what the Americans are doing.

The situation is somewhat different for Europe.

Ryan Chilcote: Speaking about President Obama, because you are the author, the architect, with President Obama, of the reset in relations. Are you disappointed by how President Obama has handled this crisis?

Dmitry Medvedev: Yes, I believe that President Obama could be more tactful politically when discussing these issues. Some decisions taken by the US Administration are disappointing. We have indeed done a lot for Russian-US relations. I believe doing so was right. The agreements that we reached with America were useful. And I’m very sorry that everything that has been achieved is now being eliminated by these decisions. Basically, we are slowly but surely approaching a new cold war that nobody needs. Why am I saying this? Because a competent politician knows how to make reserved, careful, subtle, wise and intelligent decisions, which, I believe, Mr Obama succeeded at for a while. But what is being done now, unfortunately, proves that the US Administration has run out of these resources. And the United States is one of the parties to suffer from this.

Ryan Chilcote: Do you recognise that economic sanctions, if they are introduced against Russia – we don’t have them yet – could lead to a very prolonged period of recession in Russia?

Dmitry Medvedev: Russia is obviously a part of the global economy. It was our goal to become one. The Russian economy has its own problems, mainly in terms of its structure. This has nothing to do with the United States or the position of the US Administration. These are our own problems and we have to deal with them. For instance, there’s the large role that commodities play in our economy. This is a fact. So we have enough problems in our economy. To be sure, sanctions don’t help, but if something is happening, it is first and foremost because our economy is not yet ready for a whole series of tests, and the task of the Government and the Russian authorities in general is to make this economy more effective and substantial.

Ryan Chilcote: Is Russia prepared for economic sanctions?

Dmitry Medvedev: Considering all the talk of sanctions, we’re reviewing different scenarios. None of them is disastrous for our economy, although some restrictions could be rather painful. There is no doubt that a country like Russia will be able to cope with any sanctions, or so-called sanctions. The question is what the United States or the world, for that matter, stands to gain. We have just recovered from the economic crisis that hit us all in 2008, the source of which traces back to the United States.

Ryan Chilcote: So what would the response be? If there are economic sanctions against Russia, how would you respond?

Dmitry Medvedev: I don’t want to speculate at this point about what our response might be. I can tell you only one thing: we certainly have a plan for what actions to take depending on how the situation develops, but in the event of a bad scenario, even though I said that we are opposed to any sanctions, our set of responses includes not only measures to improve our economy in general, but also measures that can be directed toward the countries in question.

Ryan Chilcote: So there could be retaliatory measures?

Dmitry Medvedev: This could be a variety of measures. I do not want to discuss them, simply because we do not believe this to be the right path. It's a dead end.

Ryan Chilcote: Just in terms of supporting Russia's own economy, if there are economic sanctions, would you do things like consider capital controls?

Dmitry Medvedev: You keep trying to elicit from me decisions that are as of yet unfounded. I’ll say it again: we are looking at different scenarios and we will act according to the circumstances. But I wouldn’t want to do this, even though, I reiterate, the Russian economy will hold up no matter what, and we will not let any country or group of countries deflect our forward progress. All I can say is that we will honour all our social commitments to the Russian people, no matter what sanctions are taken against us. There’s no doubt about it: Russia is a rich country, and we are able to control the situation.

Ryan Chilcote: Here’s the last question. I won’t keep you on this issue for long. MasterCard, Visa and threats from SWIFT… Do you believe they are a problem for you at all? This might be a long discussion, but MasterCard and Visa, as you are aware, have already suspended the provision of some of their services for a short time. How concerned are you about SWIFT, Visa, MasterCard…these financial instruments being used as part of sanctions against Russia?

Dmitry Medvedev: This is a question I would like to talk about for a little longer, if you don’t mind. In fact, a great number of our people are used to using foreign payment systems, mainly Visa and MasterCard, but also American Express. Other electronic payment systems are also widely used.

Now let me speculate over what happened. I will not be focusing on the sanctions and political decisions, which are considered an act of Parliament or an act of God in Anglo-Saxon law. Let’s look at this issue from another perspective. I am an ordinary holder of an international bank card – to be more precise, a Russian card issued by a foreign payment system. By the way, there are around 200 million cards of this type in this country – more than the population count. I would like to stress that I do not have a relationship with a foreign state. I have a relationship with the bank that issued my card. And it never occurred to me that my payments depend on the political stance of a foreign state. Therefore, I would like to note that in the context of our law – and, I’m sure, also US and EU law – what Visa and MasterCard did was a direct violation of their contract with Russian clients – not a bank, but concrete individuals who trusted these payment systems. If I were a lawyer, which I’m unfortunately not at the moment, I would have gladly spent my time and effort to take these payment systems to court. I think that this is a gross violation of effective contracts and agreements. As far as I can see, our partners at Visa and MasterCard are aware of the weakness of their position, but they had to take this decision upon the recommendation of the Treasury Department and the State Department.

I’d like to remind you that the world is monitoring this conflict because if I were a Chinese or Brazilian, I’d think: Why should I carry cards that largely depend on the stance of the US administration? Better choose the Chinese way. As you know, our Chinese partners are developing a national payment system, which, considering the global nature of the Chinese economy, is already influencing global payment systems.

In other words, this is a very bad precedent, but not for Russia, although Russians were not pleased when they had to transfer their accounts to other banks. It is bad for these companies, for MasterCard, Eurocard, and Visa.

So, we don’t want to break off any ties. We want MasterCard and Visa to stay and work in Russia. That said, they must honour their obligations, not in relation to Russia, but towards individual clients who use their cards.

Ryan Chilcote: Russia has already taken measures that some analysts say will cost MasterCard and Visa more money than it's worth to be in Russia. Aren't you concerned that Visa and MasterCard – which, as you said yourself, were just following orders, in a sense, from the Treasury in the United States – could leave the Russian market?

Dmitry Medvedev: I would like to reiterate that we do not want Visa or MasterCard to leave Russia. Overall, our cooperation with them has been quite productive. However, I believe that before taking such decisions, these companies should have thought about the fact that such actions – responding in such an awkward manner to official requests – undermine trust in them. They should have explained to their government that it should not act in this manner, since such acts by the government of the United States of America disrupts the business of Visa and MasterCard, as well as its own business.

Regarding the price they have to pay. It is true that amendments to the law on the payment system have been enacted in Russia stipulating certain deposits, which are specific amounts of money that must be placed in Russia. The Central Bank, our commercial banks, Visa and Mastercard are currently discussing this. I don’t want to dramatise the situation, but you will agree that after what our respected partners did in relation to some Russian banks there must be some response.

Ryan Chilcote: What do you think about the US telling many CEOs who were planning to go to the St Petersburg forum that they shouldn't go, and that many of them won't go? And not just US CEOs, but European CEOs as well won't be going to the forum. What do you think about that?

Dmitry Medvedev: I think this is bad. It reminds me of the decisions made in this country during the Leonid Brezhnev period. Business interests suffer because of ideology. You should ask these CEOs themselves – I have actually met some of them – from the US and Europe if they are happy about these decisions. Why do they have to sacrifice their business interests for the sake of some strange sense of solidarity?

Ryan Chilcote: That puts them in a difficult position because they want to make money, on the one hand, but they don’t want to go against their government’s wishes, on the other hand.

Dmitry Medvedev: Exactly. So, this is bringing ideology to market relations and the economy, which is exactly what the Soviet Union did in the past, when it adopted bans on trade with particular countries because their ideology didn’t suit the government. This is exactly what the US administration is doing now. This is a path to a dead end. It is destroying international economic ties and will affect the interests of US and European business. We are not dramatising the situation. Some businesspeople will attend the forum anyway; deputy CEOs, if not their bosses, will come. We will continue our dialogue, and there will be no hysterics on our part.

But this is very bad, and this is a very short-sighted stance that strongly reminds me of the Soviet government’s stance. It’s as if we had exchanged places, which is very bad.

There is one more thing I’d like to say, since you keep talking about sanctions. I’d like to remind you that no sanctions were introduced against MPs even in the most difficult periods of US-Soviet relations, like during the Cuban missile crisis or when the decision to deploy troops in Afghanistan was taken. We maintained contacts at the top political level. By enacting such sanctions, our US and European partners are destroying the very fabric of international relations. Are they trying to scare us? This will lead nowhere. Once a new administration comes to power in the United States and a new president takes office after Obama, these sanctions will be forgotten. In the end, nobody stands to win.

Ryan Chilcote: I have to ask you about the Internet, and I have to start with a slightly provocative question. Do you agree with President Putin that the Internet is a CIA project?

Dmitry Medvedev: My answer is yes and no. It is true that the Internet was born within defence-related structures. As far as I know, it was DARPA, not the CIA. What this means is that, at the outset, this network served a defence purpose. But afterwards, it grew into what is called the World Wide Web, serving as a universal phenomenon, bringing together huge numbers of people. I have never made an ideal out of the Internet, but I do believe that there is no other thing in the world with such a great unifying potential, since it creates communication opportunities, and it should be properly appreciated.

Ryan Chilcote: You say that it has to be valued, but can you guarantee that Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, will be working in Russia in a year's time? Because, as you are well aware, a Russian official not too long ago said that they may have to be closed.

Dmitry Medvedev: This was just a poor choice of words by an executive from an oversight department. Perhaps, he should have considered his words more carefully before speaking. The issue is fairly simple: everyone who works in the Russian segment of the Internet must comply with Russian regulations. That’s not debatable. It doesn't mean they have to be part of the Russian Internet, but they do have to comply with Russian regulations. This applies to Twitter and Facebook as well. By the way, my colleagues told me today that they always maintain productive cooperation with the Russian authorities if we point to a violation of Russian law.

Again, it's part of the worldwide history of communications. Millions of Russians use social media. I use it as well, I believe that it’s a good and useful thing; therefore, on the one hand, there must be compliance with Russian laws, but on the other hand, there should be freedom of access to information that is not at odds with the law. Consider that we have our own social media as well, which are also quite popular, such as VKontakte, which has tens of millions of users in Russia, Ukraine and other countries.

Ryan Chilcote: You mentioned VKontakte. Pavel Durov – the Zuckerberg, many say, of Russia, the founder of VKontakte – said that Russia is no longer a place that is conducive to doing business in the Internet; that this is not a free place for innovation in the Internet, and he has left Russia. What do you think about that?

Dmitry Medvedev: It’s difficult for me to discuss Mr Durov’s motives. I’ve met him only once, in this very room, where we discussed development prospects. He is very talented, but like every talented person he has many illusions. As far as I know, he had an argument with the company’s shareholders and his business partners and, as a result, sold his shares. As it often happens, he cited political circumstances to explain his actions and started another project. It was his decision, but VKontakte will continue to exist. It is a completely open platform. Your Russian is excellent, so you can see for yourself what it’s like. There is no censorship; everything is just the same as on Facebook because these two media are similar. The only thing is I think it is important for people using any social media to be a little more polite so that social media is a more civilised environment. This is true for both VKontakte and Facebook as well as for some others.

Ryan Chilcote: It's interesting you bring up that point, because CalPERS, the California pension system, which manages just over a quarter trillion dollars, decided that they would no longer invest in VKontakte because of concerns that VKontakte continued to show attacks on gays. You know the story, right?

Dmitry Medvedev: To be honest, I was not familiar with this story. You brought it to my attention.

Ryan Chilcote: Do you recognise that a lot of the political and social decisions that are made in Russia are having big impacts on business and investment – not just Ukraine, but the law on so-called untraditional values in Russia – and is that okay?

Dmitry Medvedev: Any political decision in some way or another influences the investment climate and business. It's senseless to argue that Russia’s decisions regarding Ukraine or Crimea did not have any impact on the business environment. The same is true for laws that are being enacted. I don’t think that such decisions are destroying the business environment, but we have to analyse their consequences. By the same token, our friends and partners in other countries should be mindful of decisions they take regarding their businesses when they introduce various sanctions against Russia. Thus, it’s a question of rationality. I agree that there are certain things we can also be reproached for, but I’d like our partners to keep this in mind as well.

Ryan Chilcote: Prime Minister Medvedev, thank you very much for your time.

Dmitry Medvedev: Thank you so much. Good luck.